A Full Epistemic Stack

Knowledge Commons for the 21st Century

We’re writing this in our personal capacity. While our work at the Future of Life Foundation has recently focused on this topic and informs our thinking here, this specific presentation of our views are our own.

Knowledge is integral to living life well, at all scales:

Individuals manage their life choices: health, career, investment, and others on the basis of what they understand about themselves and their environments.

Institutions and governments (ideally) regulate economies, provide security, and uphold the conditions for flourishing under their jurisdictions, only if they can make requisite sense of the systems involved.

Technologists and scientists push the boundaries of the known, generating insights and techniques judged valuable by combining a vision for what is possible with a conception of what is desirable (or as proxy, demanded).

More broadly, societies negotiate their paths forward through discourse which rests on some reliable, broadly shared access to a body of knowledge and situational awareness about the biggest stakes, people’s varied interests in them, and our shared prospects.

(We’re especially interested in how societies and humanity as a whole can navigate the many challenges of the 21st century, most immediately AI, automation, and biotechnology.)

Meanwhile, dysfunction in knowledge-generating and -distributing functions of society means that knowledge, and especially common knowledge, often looks fragile1. Some blame social media (platform), some cynical political elites (supply), and others the deplorable common people (demand).

But reliable knowledge underpins news, history, and science alike. What resources and infrastructure would a society really nailing this have available?

Among other things, we think its communication and knowledge infrastructure would make it easy for people to learn, check, compare, debate, and build in ways which compound and reward good faith. This means tech, and we think the technical prerequisites, the need, and the vision for a full epistemic stack2 are coming together right now. Some pioneering practitioners and researchers are already making some progress. We’d like to nurture and welcome it along.

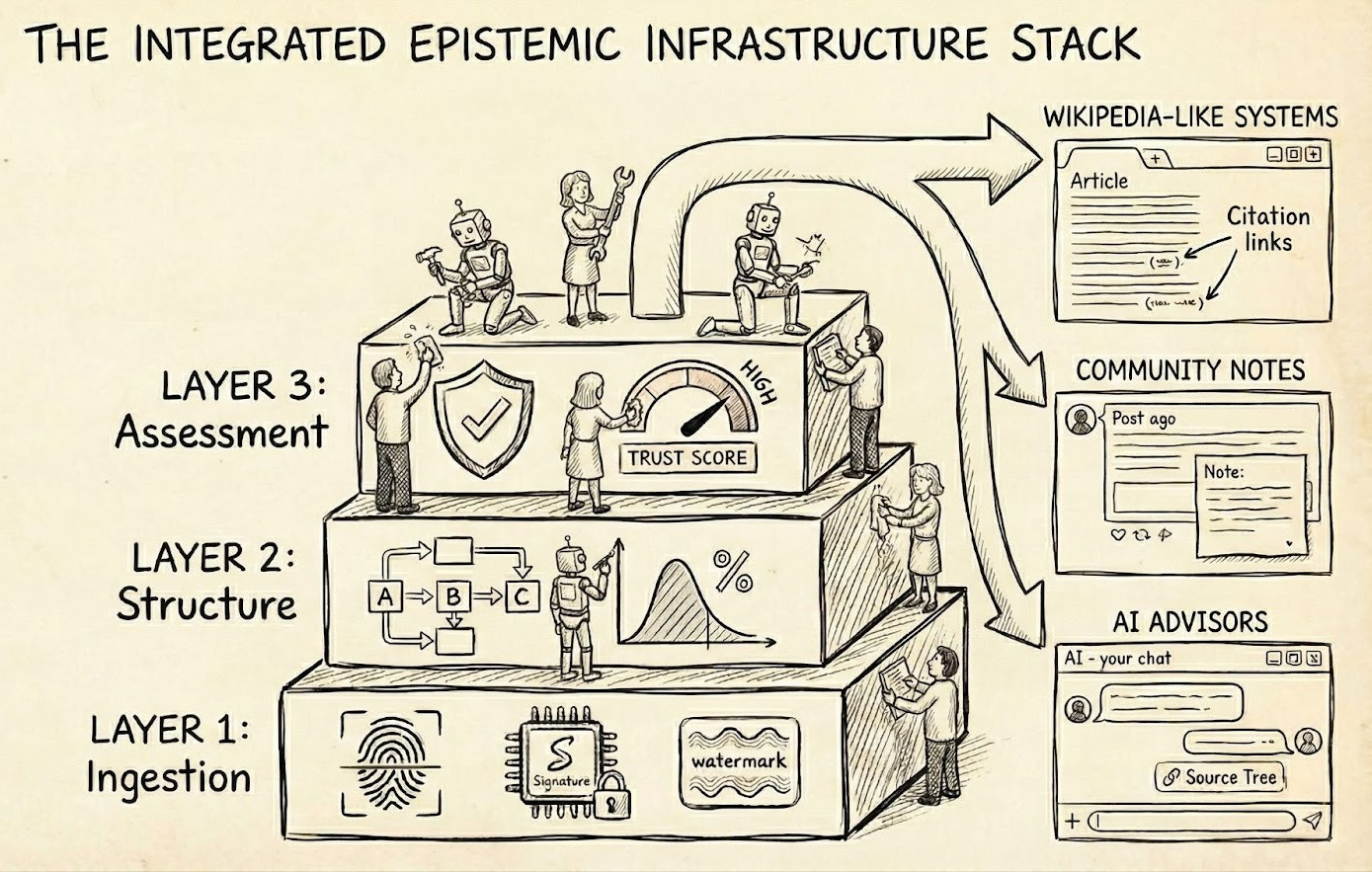

In this short series, we’ll outline some ways we’re thinking about the space of tools and foundations which can raise the overall epistemic waterline and enable us all to make more sense. In this first post, we introduce frames for mapping the space —3 different layers for info gathering, structuring into claims and evidence, and assessment — and potential end applications that would utilize the information.

A full what?

A full epistemic stack. Epistemic as in getting (and sharing) knowledge. Full stack as in all of the technology necessary to support that process, in all its glory.

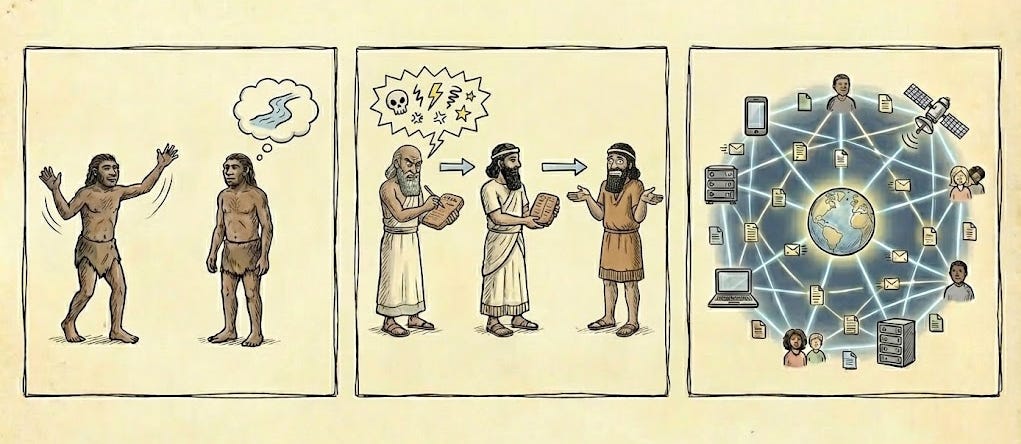

What’s involved in gathering information and forming views about our world? Humans aren’t, primarily, isolated observers. Ever since the Sumerians and their written customer complaints4, humans have received information about much of their our world from other humans, for better or worse. We sophisticated modern beings consume information diets transmitted across unprecedented distances in space, time, and network scale.

With an accelerating pace of technological change and with potential information overload at machine speeds, we will need to improve our collective intelligence game to keep up with the promise and perils of the 21st century.

Imagine an upgrade. People faced with news articles, social media posts, research papers, chatbot responses, and so on can trivially trace their complete epistemic origins — links, citations, citations of citations, original data sources, methodologies — as well as helpful context (especially useful responses, alternative positions, and representative supporting or conflicting evidence). That’s a lot, so perhaps more realistically, most of the time, people don’t bother… but the facility is there, and everyone knows everyone knows it. More importantly, everyone knows everyone’s AI assistants know it (and we know those are far less lazy)! So the waterline of information trustworthiness and good faith discourse is raised, for good. Importantly, humans are still very much in the loop — to borrow a phrase from Audrey Tang, we might even say machines are in the human loop.

Some pieces of this are already practical. Others will be a stretch with careful scaffolding and current-generation AI. Some might be just out of reach without general model improvements… but we think they’re all close: 2026 could be the year this starts to get real traction.

Does this change (or save) the world on its own? Of course not. In fact we have a long list of cautionary tales of premature and overambitious epistemic tech projects which achieved very few of their aims: the biggest challenge is plausibly distribution and uptake. (We will write something more about that later in this series.) And sensemaking alone isn’t sufficient! — will and creativity and the means to coordinate sufficiently at the relevant scale are essential complements. But there’s significant and robust value to improving everyone’s ability to reason clearly about the world, and we do think this time can be different.

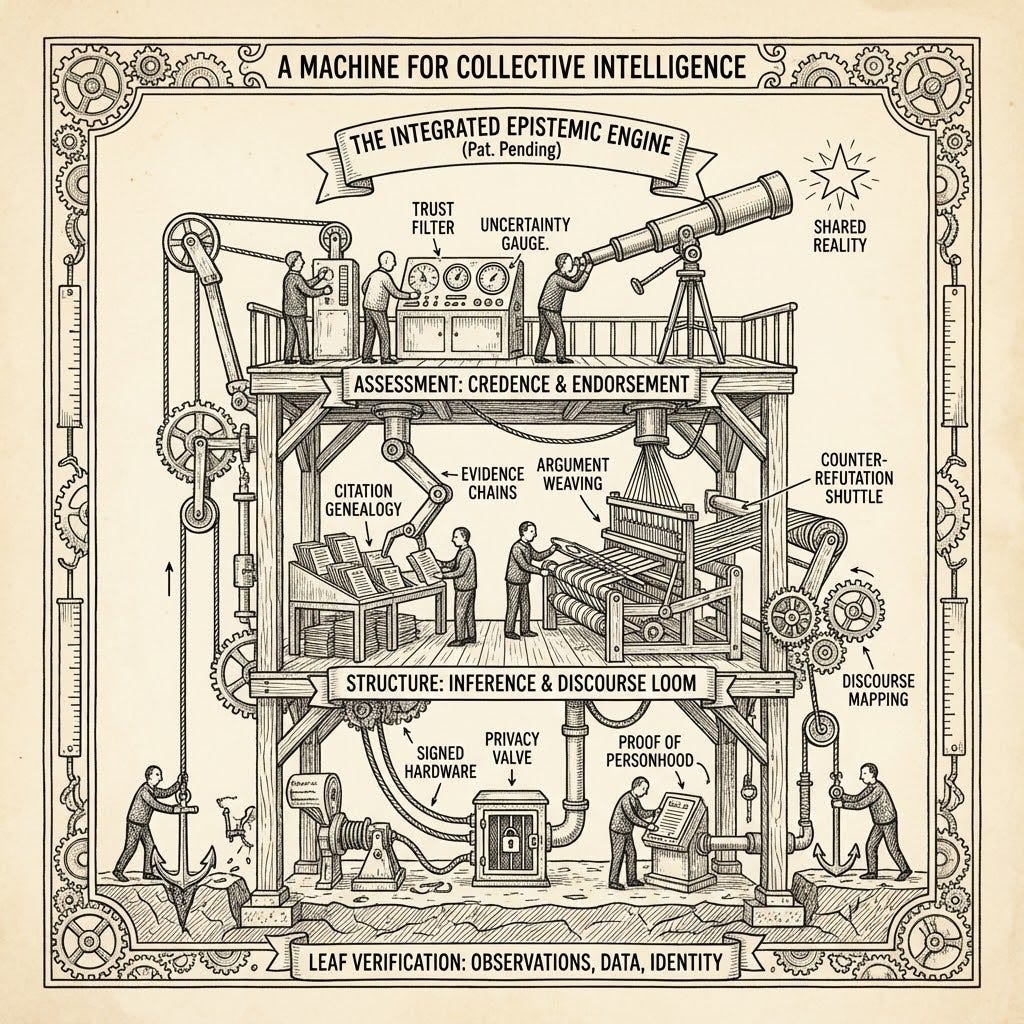

Layers of a foundational protocol

Considering the dynamic message-passing network of human information processing, we see various possible hooks for communicator-, platform-, network-, and information-focused tech applications which could work together to improve our collective intelligence.

We’ll briefly discuss some foundational information-focused layers together with user experience (UX) and tools which can utilise the influx of cheap clerical labour from LMs, combined with intermittent judgement from humans, to make it smoother and easier for us all to make sense.

All of these pieces stand somewhat alone — a part of our vision is an interoperable and extensible suite — but we think implementations of some foundations have enough synergy that it’s worth thinking of them as a suite. We’ll outline where we think synergies are particularly strong. In later posts we’ll look at some specific technologies and examples of groups already prototyping them; for now we’re painting in broad strokes some goals we see for each part of the stack.

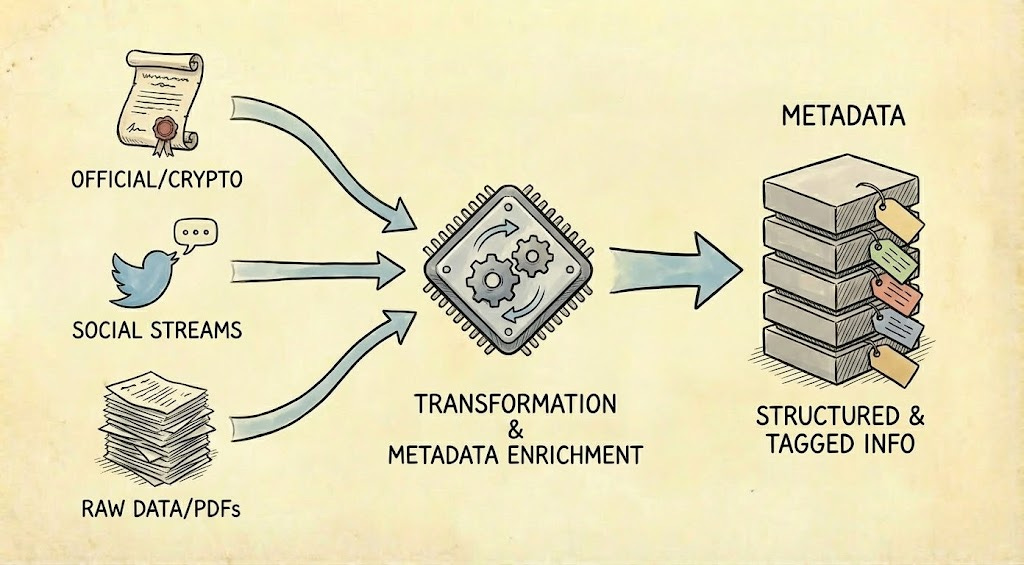

Ingestion: observations, data, and identity

Ultimately grounding all empirical knowledge is some collection of observations… but most people rely on second-hand (and even more indirect) observation. Consider the climate in Hawaii. Most people aren’t in a position to directly observe that, but many have some degree of stake in nonetheless knowing about it or having the affordance to know about it.

For some topics, ‘source? Trust me bro,’ is sufficient: what reason do they have to lie, and does it matter much anyway? Other times, for higher stakes applications, it’s better to have more confirmation, ranging from a staked reputation for honesty to cryptographic guarantee5.

Associating artefacts with metadata about origin and authorship (and further guarantees if available) can be a multiplier on downstream knowledge activities, such as tracing the provenance of claims and sources, or evaluating track records for honesty. Thanks to AI, precise formats matter less, and tracking down this information can be much more tractable. This tractability can drive the critical mass needed to start a virtuous cycle of sharing and interoperation, which early movers can encourage by converging on lightweight protocols and metadata formats. In true 21st Century techno-optimist fashion, we think no centralised party need be responsible for storing or processing (though distributed caches and repositories can provide valuable network services, especially for indexing and lookup6).

Structure: inference and discourse

Information passing and knowledge development involve far more than sharing basic observations and datasets between humans. There are at least two important types of structure: inference and discourse.

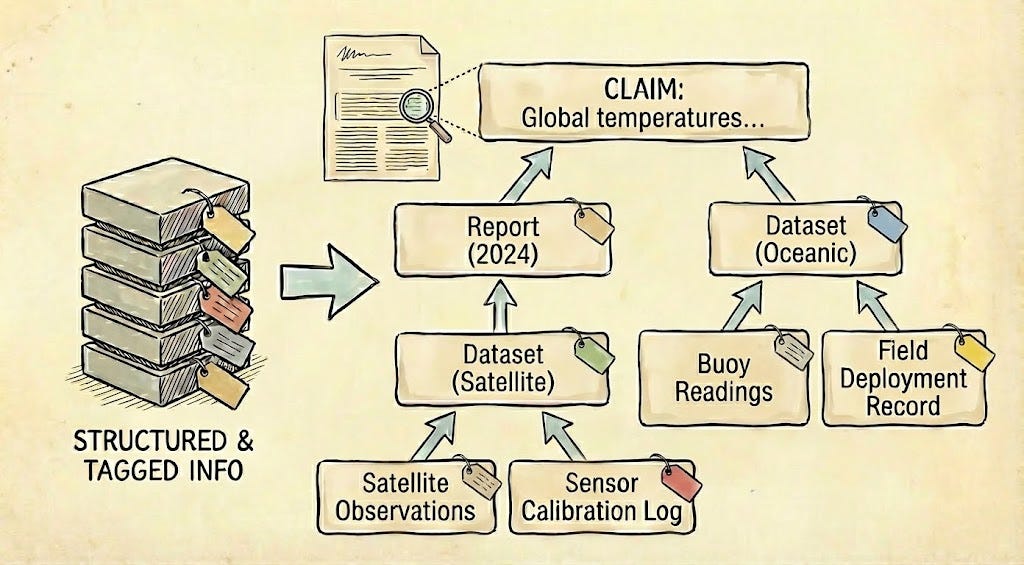

Inference structure: genealogy of claims and supporting evidence (Structure I)

Ideally perhaps, raw observations are reliably recorded, their search and sampling processes unbiased (or well-described and accounted for), inferences in combination with other knowledge are made, with traceable citations and with appropriate uncertainty quantification, and finally new traceable, conversation-ready claims are made.

We might call this an inference structure: the genealogy and epistemic provenance of given claims and observations, enabling others to see how conclusions were reached, and thus to repeat or refine (or refute) the reasoning and investigation that led there.

Of course in practice, inference structure is often illegible and effortful to deal with at best, and in many contexts intractable or entirely absent. We are presented with a selectively-reported news article with a scant few hyperlinks, themselves not offering much more context. Or we simply glimpse the tweet summary with no accompanying context.

Even in science and academia where citation norms are strongest, a citation might point to a many-page paper or a whole book in support of a single local claim, often losing nuance or distorting meaning along the way, and adding much friction to the activity of assessing the strength of a claim7.

How do tools and protocols improve this picture? Metascience reform movements like Nanopublications strike us as a promising direction.

Already, LM assistance can make some of this structure more practically accessible, including in hindsight. A lightweight sharing format and caches for commonly accessed inference structure metadata can turn this into a reliable, cheap, and growing foundation: a graph of claims and purported evidence, for improved further epistemic activity like auditing, hypothesis generation, and debate mapping.

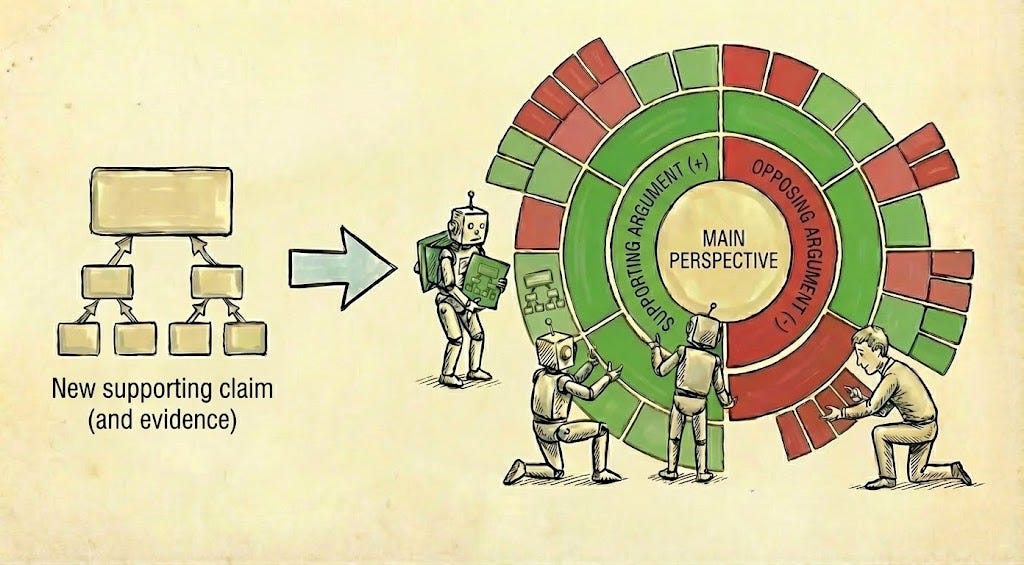

Discourse: refinement, counterargument, refutation (Structure II)

Knowledge production and sharing is dynamic. With claims made (ideally legibly), advocates, detractors, investigators, and the generally curious bring new evidence or reason to the debate, strengthening or weakening the case for claims, discovering new details, or inferring new implications or applications.

This discourse structure associates related claims and evidence, relevant observations which might not have originally been made with a given topic in mind, and competing or alternative positions.

Unfortunately in practice, many arguments are made and repeated without producing anything (apart from anger and dissatisfaction and occasional misinformation), partly because they’re disconnected from discourse. This is valuable both as contextual input (understanding the state of the wider debate or investigation so that the same points aren’t argued ad infinitum and people benefit from updates), and as output (propagating conclusions, updates, consensus, or synthesis back to the wider conversation).

This shortcoming holds back science, and pollutes politics.

Tools like Wikipedia (and other encyclopedias), at their best, serve as curated summaries of the state of discourse on a given topic. If it’s fairly settled science, the clearest summaries and best sources should be made salient (as well as some history and genealogy). If it’s a lively debate, the state of the positions and arguments, perhaps along with representative advocates, should be summarised. But encyclopedias can be limited by sourcing, available cognitive labour and update speed, one-size-fits-all formatting, and sometimes curatorial bias (whether human or AI).8

Similar to the inference layer, there is massive untapped potential to develop automations for better discourse tracking and modeling. For example, LLMs doing literature reviews can source content from a range of perspectives for downstream mapping. Meanwhile, relevant new artefacts can be detected and ingested close to realtime. We don’t need to agree on all conclusions — but we can much more easily agree on the status of discourse: positions on a topic, the strongest cases for them, and the biggest holes9. Direct access as well as helpful integrations with existing platforms and workflows can surface the most useful context to people as needed, in locally-appropriate format and level of detail.

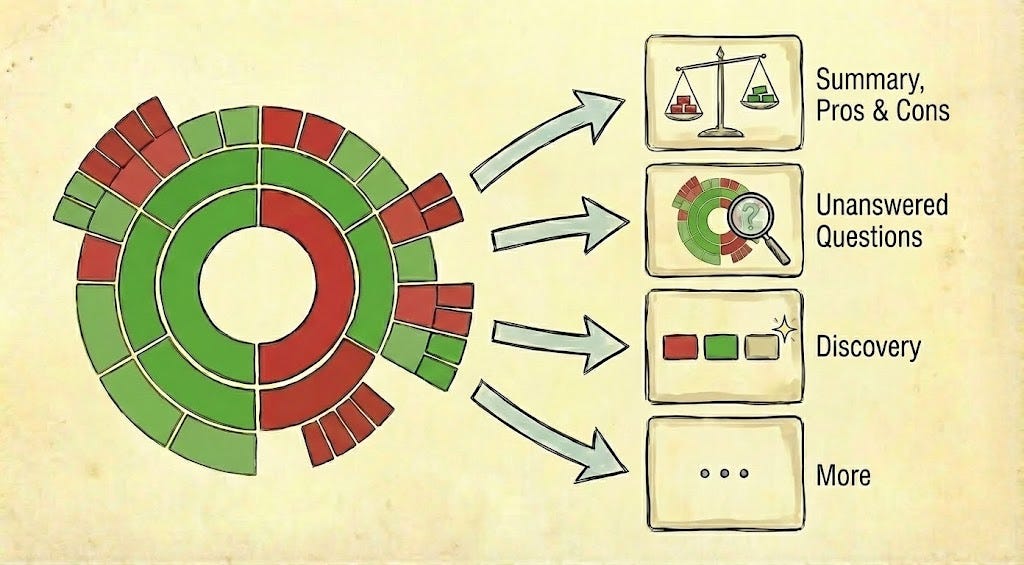

Assessment: credence, endorsement, and trust

Claims and evidence, together with counter claims and an array of perspectives (however represented), give some large ground source of potential insight. But at a given time and for a given person there is some question to be answered: reaching trusted summaries and positions.

Ultimately consumers of information sources come to conclusions on the basis of diverse signals: compatibility with their more direct observations, assessment of the trustworthiness and reliability (on a given topic) of a communicator, assessment of methodological reasonableness, weighing and comparing evidence, procedural humility and skepticism, explicit logical and probabilistic inference, and so on. It’s squishy and diverse!

We think some technologies are unable to scale because they’re too rigid in assigning explicit probabilities, or because they enforce specific rules divorced from context. This fails to account for real reasoning processes and also can work against trust because people (for good and bad reasons) have idiosyncratic emphases in what constitutes sensible reasoning.

We expect that trust should be a late-binding property (i.e. at the application layer), to account for varied contexts and queries and diverse perspectives, interoperable with minimally opinionated structure metadata. That said, squishy, contextual, customisable reasoning is increasingly scalable and available for computation! So caches and helpful precomputations for common settings might also be surprisingly practical in many cases.

With foundational structure to draw from, this is where things start to substantially branch out and move toward the application layer. Some use cases, like summarisation, highlighting key pros and cons and uncertainties, or discovery, might directly touch users. Other times, downstream platforms and tools can integrate via a variety of customized assessment workflows.

Beyond foundations: UX and integrations

Foundations and protocols and epistemic tools sound fun only to a subset of people. But (almost) everyone is interested in some combination of news, life advice, politics, tech, or business. We don’t anticipate much direct use by humans of the epistemic layers we’ve discussed. But we already envision multiple downstream integrations into existing and emerging workflows: this motivates the interoperability and extensibility we’ve mentioned.

A few gestures:

Social media platforms struggle under adversarial and attentional pressures. But distributed, decentralised context-provision, like the early success stories in Community Notes, can serve as a widely-accessible point of distribution (and this is just one form factor among many possible). In turn, foundational epistemic tooling can feed systems like Community Notes.

More speculatively, social-media-like interfaces for uncovering group wisdom and will at larger scales while eliciting more productive discourse might be increasingly practical, and would be supported by this foundational infrastructure.

Curated summaries like encyclopedias (centralised) and Wikipedia (decentralised) are often able to give useful overviews and context on a topic. But they’re slow, don’t have coverage on demand, offer only one-size-fits-all, and are sometimes subject to biases. Human and automated curators could consume from foundational epistemic content and react to relevant updates responsively. Additionally, with discourse and inference structure more readily and deeply available, new, richly-interactive and customisable views are imaginable: for example enabling strongly grounded up- and down-resolution of topics on request10, or highlighting areas of disagreement or uncertainty to be resolved.

Authors and researchers already benefit from search engines, and more recently ‘deep research’ tooling. Integration with easily available relational epistemic metadata, these uplifts can be much more reliable, trustworthy, and effective.

Emerging use of search-enabled AI chatbots as primary or complementary tools for search, education, and inquiry means that these workflows may become increasingly impactful. Equipping chatbots with access to discourse mapping and depth of inference structure can help their responses to be grounded and direct people to the most important points of evidence and contention on a topic.

Those who want to can already layer extensions onto their browsing and mobile internet experiences. Having always-available or on-demand highlighting, context expandables, warnings, and so on, is viable mainly to the extent that supporting metadata are available (though LMs could approximate these to some degree and at greater expense). More speculatively, we might be due a browser UX exploration phase as more native AI integration into browsing experiences becomes practical: many such designs could benefit from availability of epistemic metadata.

How? Why now?

If this would be so great, why has nobody done it already? Well, vision is one thing, and we could also make a point about underprovision of collective goods like this. But more relevant, the technical capacity to pull off this stack is only really just coming online. We’re not the first people to notice the wonders of language models.

First, the not inconsiderable inconveniences of the core epistemic activities we’ve discussed are made less overwhelming by, for example, the ability of LLMs to digest large amounts of source information, or to carry out semi-structured searches and investigations. Even so, this looks to us like mainly a power-user approach, even if it came packaged in widely available tools similar to deep research, and it doesn’t naively contribute to enriching knowledge commons. We can do better.

With a lightweight, extensible protocol for metadata, caching and sharing of discovered inference structure and discourse structure becomes nearly trivial11. Now the investigations of power users (and perhaps ongoing clerical and maintenance work by LLM agents) produce positive epistemic spillover which can be consumed in principle by any downstream application or interface, and which composes with further work12. Further, the risks of hallucinated or confabulated sources (for LMs as with humans) can be limited by (sometimes adversarial) checking. The epistemic power is in the process, not in the AI.

Various types of openness can bring benefits: extensibility, trust, reach, distribution — but can also bring challenges like bad faith contributions (for example omitting or pointing to incorrect sources) or mistakes. Tools and protocols at each layer will need to navigate such tradeoffs. One approach could have multiple authorities akin to public libraries taking responsibility for providing living, well-connected views over different corpora and topics — while, importantly, providing public APIs for endorsing or critiquing those metadata. Alternatively, perhaps anyone (or their LLM) could check, endorse, or contribute alternative structural metadata13. Then the provisions of identity and endorsement in an assessment layer would need to solve the challenges of filtering and canonicalisation.

In specific epistemic communities and on particular topics, this could drive much more comprehensive understanding of the state of discourse, pushing the knowledge frontier forward faster and more reliably. Across the broader public, discourse mapping and inference metadata can act against deliberate or accidental distortion, supporting (and incentivising) more good faith communication.

Takeaways

Knowledge, especially reliable shared knowledge, helps humans individually and collectively be more right in making plans and taking action. Helping people better trust the ways they get and share useful information can deliver widespread benefits as well as defending against large-scale risk, whether from mistakes or malice.

We communicate at greater scales than ever, but our foundational knowledge infrastructure hasn’t scaled in the same way. We see a large space of opportunities to improve that — only recently coming into view with technical advances in AI and ever-cheaper compute.

This is the first in what will be a series exploring one corner of the design landscape for epistemic tech: there are many uncertainties still, but we’re excited enough that we’re investigating and investing in pushing it forward.

We’ll flesh out more of our current thinking on this stack in future entries in this series, including more on existing efforts in the space, interoperability, and core challenges here (especially distribution).

Please get in touch if any of this excites or inspires you, or if you have warnings or reasons to be skeptical!

Thanks to our colleagues at the Future of Life Foundation, and to several epistemic tech pioneers for helpful conversations feeding into our thinking.

You might think this is a new or worsening phenomenon, or you might think it perennial. Either way, it’s hard to deny that things would ideally be much better. We further think there is some urgency to this, both due to rising stakes and due to foreseeable potential for escalating distortion via AI.

Improved terminological branding sorely needed

Coauthor Oly formerly frequently used single hyphens for this sort of punctuation effect, but coincidentally started using em-dashes recently when someone kindly pointed out that it’s trivial to write them while drafting in google docs. This entire doc is human-written (except for images). Citation: trust us.

or perhaps as early as Homo erectus and his supposed pantomime communication, or even earlier

Some such guarantees might come from signed hardware, proof of personhood, or watermarking. We’re not expecting (nor calling for!) all devices or communications to be identified, and not necessarily expecting increased pervasiveness of such devices. Even where the capability is present on hardware, there are legitimate reasons to prefer to scrub identifying metadata before some transmissions or broadcasts. In a related but separate thread of work, we’re interested in ways to expand the frontier of privacy x verification, where we also see some promising prospects.

Compare search engine indexes, or the Internet Archive.

Relatedly, but not necessarily as part of this package, we are interested in automating and scaling the ability to quickly identify rhetorical distortion or unsupported implicature, which manifests in science as importance hacking and in journalism as spin, sensationalism, and misleading framing.

Wikipedia, itself somewhere on the frontier of human epistemic infrastructure, becomes at its weakest points a battleground and a source of contention that it’s not equipped to handle in its own terms.

This gives open, discoverable discourse a lot of adversarial robustness. You can do all you like to deny a case, malign its proponents, claim it’s irrelevant… but these are all just new (sometimes valuable!) entries in the implicit ‘ledger’ of discourse on a topic. This ‘append-only’ property is much more robust than an opinionated summary or authoritative canonical position. Of course append-only raises practical computational and storage concerns, and editorial bias can re-enter any time summarisation and assessment is needed.

Up- and down-resolution is already cheaply available on request: simply ask an LLM ‘explain this more’ or ‘summarise this’. But the process will be illegible, hard to repeat, and lack the trust-providing support of grounding in annotated content.

Storage and indexing is the main constraint to caching and sharing, but the metadata should be a small fraction of what is already stored and indexed in many ways on the internet.

How to fund the work that produces new structure? In part, integration with platforms and workflows that people already use. In part, this is a public good, so we’re talking about philanthropic and public goods funding. In some cases, institutions and other parties with interest in specific investigations may bring their own compute and credits.

Does this lack of opinionated authority on canonical structure defeat the point of epistemic commons? Could a cult, say, provision their own para-epistemic stack? Probably — in fact in primitive ways they already do — but it’d be more than a little inconvenient, and we think that availability of epistemic foundation data and ideally integration into existing platforms, especially because it’s unopinionated and flexible in terms of final assessment, can drive much improvement in any less-than-completely adversarially cursed contexts.